The mind alone is more than sufficient to explain all the phenomena observed by Behaviourism.

Behaviourism is superficial, superfluous, and unnecessary. Simply put, creatures do not operate without a mind, which our understanding of is more than sufficient enough to completely replace and render Behaviourism irrelevant.

Our current understanding of the mind using evolutionary biology and neuroscience explains not only far more behaviour but with more accuracy than Behaviourism will allow.

A model of cognitive shortcuts, heuristics, correlational models—phenomena unique to our minds and otherwise not present in artifically-constructed intelligence, is sufficient to explain the observations found by Behaviourism.

The correlational model

Do we not simply assign a mental correlation coefficient to phenomena and react accordingly to the probability? Why does behaviour have to be certain—why does everything have to be set in stone? Human emotion drives us to create dichotomies for the sake of convenience and speed, but do our minds really not see beyond that—do we not assess the probability of events?

Does the existence of confirmation and selection bias (along with other informal fallacies and biases) not prove that our minds really do value probability, to the extent that we would “intentionally” mislead ourselves for the sake of wanting to believe something?

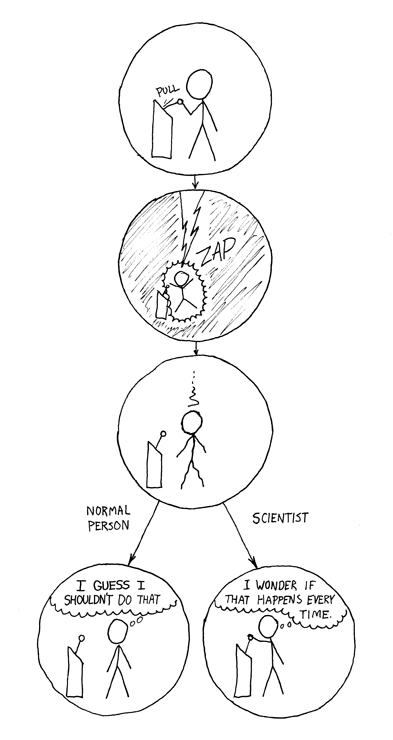

Take the state of becoming unconditioned, for example: creatures become unconditioned because their internal memory—their record—of the events become diluted with sample events that are otherwise identical but do not lead to the expected outcome, eventually reducing the correlation to a level where it becomes more likely (n.b. the threshold varies according to the individual and species and isn’t necessarily the same each time due to lack of perfect rationality) for the correlation to be weak to non-existent.

Operant conditioning

Operant conditioning is merely a mental model of the world works, at least for that creature, though mental models are far more than the nature of Behaviourism will allow.

Note that Behaviourism experiments are simplistic, one-dimensional, and do not involve any challenging situations such as making a morally-ambiguous choice. It would be impossible to avoid the idea of a mind to explain the results from such an experiment.

If you rewarded someone every time they performed a categorically evil act, are they more likely to do it the more it’s reinforced, or are they—contrary to the theory—less likely to continue? Do people feel guilt? Regret?

Where does that come from? Nobody’s punishing them, right? Yet, it seems almost as if they feel punished each time they do it anyway—almost as if… they’re punishing themselves. Why would they do that? How can one explain that without the concept of a mind?

Another phenomenon mentioned is the tendency for extremely salient events to immediately condition an individual even after only one exposure. However, it doesn’t explain why disorders like masochism exist, and why a group of people get to decide, universally, what good and bad is (what reward and punishment is).

In addition, that phenomenon is also easily described using the availability heuristic, further rendering Behaviourism redundant.

A short rant about CBT

If this were a hit on Behaviourism it would be nothing more than low-hanging fruit given how old Behaviourism is and how nonsensical anything can sound when discussed independently outside of context.

Nobody really believes Behaviourism anymore—at least, not in its original form, which is another fantastic sign of scientific progress. Maybe one day we’ll also kick the “B” out of “CBT” and rid the ubiquitous psychotherapy method of Behaviourism’s weaknesses like their pre-defined worldviews and universal definitions of good and bad (reward and punishment).

And then, we’ll have psychotherapy that better corresponds to reality without ignoring philosophy like a skeleton in the closet—psychotherapy that is far more compassionate and understanding; psychotherapy that doesn’t automatically assume that any worldview that doesn’t fall into their definition of “good” is “wrong”.

I wish to live to see the day I find a psychotherapy method based on compassion and realism instead of pseudo-rational rejection and dismissal. It makes no sense why so many CBT practitioners still believe in contradictory, dualistic theories, yet it also explains why compassion and understanding is so rarely found when faced with challenging scientific and philosophical dilemmas.

I believe the population most likely to be at risk are the highly intelligent (or gifted), who often have challenging and unique cases of depression due to their advanced and profound insights, as they’re most likely to be misunderstood (reinforcing their depression) and dismissed, for their concerns can’t possibly be correct or rational.

Depressive realism in and of itself is difficult to test and remains inconclusive, but why not throw a bone and test it out? Why not evaluate that person’s environment or listen to their concerns, then change that environment accordingly and see whether they still remain the same?

Are they really depressed because they’re irrational? Or are they depressed precisely because they are rational? Can depression ever be justified—is there ever a situation where it would be irrational to not be depressed? If the answer is no, I would suggest going back to the drawing board and reevaluating falsifiability instead of continuing with this pernicious form of psychotherapy.

Closing remarks

The many CBT and “mindfulness” practitioners I’ve seen or encountered myself are often quite unwilling to listen to reason outside of mindlessly browsing abstracts and throwing studies at their interlocutor claiming that the studies “prove” that they’re right (a discussion that will be left for another day), this causes me a bit of worry as I imagine them finding my article and posting a nasty comment (with links to several studies) about how wrong I am (followed by more links to studies).

CBT’s success rate isn’t that high. Sure, it’s relatively high, but I believe it would be even higher (with a lower relapse rate) if it were to adopt a more compassionate and reasonable stance by abandoning the pre-definitions of good and bad and allowing clients’ reasoning to be considered and addressed. Without sufficient consideration for philosophy and reasoning, CBT is nothing more than a crude, brute-force method of addressing mental illnesses like depression (brute-force can be a surprisingly-effective strategy, but that’s a discussion for another day).

Philosophy (and philosophical reasoning) was something that came very naturally to me ever since I was young, so I can’t claim to understand why someone would be uninterested in something I find so intrinsically interesting just like how I can’t begin to fathom why someone would find something like soccer so interesting.

Just like that soccer fan, I still love the idea of everyone sharing my interest one day, even if it’s not realistically possible or even necessarily optimal.

There are no sides in philosophy, so just take any.