Nietzsche’s intellectual conscience is both simple yet difficult for many to understand. Here is my interpretation of it.

Instead of presenting it by description alone, I will try and demonstrate an example of an “honest” thought process using practical, immediately-applicable questions.

It will be a series of many questions (sometimes repeated for emphasis) in no-particular order, separated only for the sake of clarity and only clarity.

The premise

I believe that Q.

Do I know that Q is correct? (a part of the intellectual “conscience” is not believing in or sharing false knowledge, hence conscience)

What have I done to make sure that Q is correct?

What do I know about Q? What is Q?

How much of Q do I know?

Honesty

Is the veracity of Q important to me/does it matter to me that Q is true?

Have I done everything to guarantee the veracity of Q?

Continued introspection

Am I being honest when I say I’ve done everything to prove that Q is true? Have I really done everything?

Have I eliminated all the factors that can influence my judgement? How objective am I?

Have I accounted for the biases I’m aware of?

Do I really know all the factors that influence me? What have I done to make sure there are no other factors influencing me?

Are there any hidden influences—such as a desire for a certain outcome—that affects my knowledge? Are there things I “choose” not to remember, even if not by conscious choice?

How much do I know about “me”, the person collecting the evidence? Can I trust this person? How honest is this person?

Have I omitted anything? Glanced over any information I disliked? Have I been reluctant to address any problems with Q?

The introspective limit

How much of me do I not know?

Is there a limit to my introspection—a part of my thought process I can never control or even notice via introspection alone? How much of my mind is “me”? If “me” isn’t my entire mind*, and if my entire mind is responsible for the belief that Q, then I cannot honestly believe that Q.

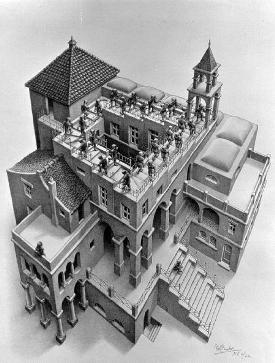

*We can see evidence of this in many modern studies with heuristics, biases, and various experiments with brain trauma victims, but a convenient example often used to quickly elucidate this point is with optical illusions:

What this means

As much as I may have glanced over the difficulty of introspection (this is not an exhaustive list), I hope these will be of some use to someone in future, even if as a target for debate.

The conclusion may imply that we should not believe in anything at all, but that’s missing a lot of its intricacies. For one, what it really means is that we cannot believe in anything with absolute certainty, unless they are factual by definition. “For example, this sentence has seven words.” is a fact by definition.

In place of this, philosophers generally prefer to use the phrase: “beyond reasonable doubt”, whenever we’re dealing with facts that are untrue by definition alone.

We can be very certain that Q, possibly beyond reasonable doubt, but we can never be absolutely certain that Q, as long as Q is, again, not a fact by definition: no sane person will (or even can) doubt that Sudoku has nine 3×3 grids, that cats don’t bark, and that seven is a prime number.

In other words, these statements are true precisely because we defined them to be so, not because we have evidence to prove it, or because we arrived at it via some impeccable chain of logic and reasoning—these facts cannot be questioned by themselves unless we challenge the definitions. For example, we could try and redefine what “Sudoku” means, what “barking” sounds like, and what a “prime number” is, but as long as the definitions remain, these statements are indisputable (but boring) facts.

But these are rather bland, and can hardly be called “opinions” or “beliefs”—the number of “suns” in “our solar system” being “one” is not an opinion, and hardly worth any debate.

Assuming that Q is more “interesting”, then the line of questions apply, with the inevitable uncertainty at the end preventing us from ever being absolutely certain that Q, only that our previous steps have helped us decide whether Q was true beyond reasonable doubt.

Closing remarks

Before we believe that Q—or worse, try convincing others that Q—we should always consider whether Q is true, and how much we’ve done to ensure that Q is true. If we have not verified it honestly first, how can we be honest in telling someone else that it’s true when we haven’t even made sure that it was true ourselves?

Even if Q turns out to correct by matter of chance, the fact we have done nothing to verify that Q is true before convincing others of it is still intellectually dishonest. In a sense, it is no different from lying and deceiving—this reckless and irresponsible sharing of knowledge. Worse still, of course, if Q turns out to be false, which happens more often than not in those who apply a blind faith to their convictions, taking wild gambles in their beliefs being true.

The world may be less uninformed than it used to be, but there’s still no reason to contribute to the problem, just like how improving climate conditions (hopefully) is no reason to start dumping litter into the sea—the world doesn’t have to be in some equilibrium of “good” and “bad”; there’s no need to pollute the world with more “bad” just because there’s too much “good”.

That said, I’m sure you’ve all noticed the elephant in the room—the glaring problem with this way of living: it’s beyond impractical. Nobody can live like this.

Luckily for us, the use of disclaimers and probabilistic statements help free us from much of this responsibility. Common methods include phrases like “scientific consensus”, “generally agreed”, “significantly high chance”, or hinging our bets on someone else by quoting famous and wise intellectuals whom we trust to be honest… right? Either way, even if their statements turned out to be wrong, your interlocutor would be best looking for them instead of you, as you didn’t “actually say it” (this is very disputable due to you choosing the quotes (like Bumblebee in the Transformers movies “speaking” through the radio), but it’s a humorous example of pushing blame around).

Anyway, in reality, most people (I hope) don’t actually pepper their sentences with disclaimers of uncertainty and encouraging others to do their own research for every line in their speech as they weren’t absolutely confident in them themselves, myself included. Contrary to making others believe them more, this level of responsibility and honestly actually undermines their credibility in a twist if ironic ignorance as people are too used to being “swindled” by other “liars” who don’t give any disclaimers and speak with excessive (often unwarranted) confidence.

As a result, critical thinking is critically important, but a good substitute if you don’t want to perform all these mental gymnastics just to believe in any particular proposition is to just limit emotional attachment to them.

By limiting emotional attachment to beliefs, we can change them much more easily and are less likely to be irrational, reckless, and irresponsible with them, circumventing much of the drawbacks of intellectual dishonesty even if only being honest to the extent of:

“I believe that Q, even if I don’t know that Q”.

Once again, for emphasis, I would like to stress the importance of always keeping at least a modicum of genuine doubt and uncertainty in every belief one has, and at least partially acknowledging the fallibility of our minds. This, along with low emotional attachment, allows us to readily adapt our beliefs to new insights and evidence, and even further in the future as we go through the many different consensuses, almost like sailing in an ocean.

Addendum: I highlight some caveats about the use of disclaimers here.