2022-13-9: Added a section to clarify my stance on “autism advocates”

So… autism isn’t real

I’ll start by saying that none of the disorders listed in the DSM are “real”—if we define real as being indisputably true and exhaustively descriptive.

What do you mean not real?

If you’re familiar with how science works, this might not be very surprising. After all science is, at its core, based on induction (or sometimes abduction), which cannot give us absolute certainty unlike deductive reasoning processes. One common example of deductive reasoning is found in syllogisms:1. Only cats meow

2. I hear meowing behind my door

3. Therefore a cat is behind my door

A syllogism relies on its premises being true, in this case if (1) is untrue (that things other than cats can make meowing sounds), then the conclusion (3) will be false. If the premises (1) and (2) are true, then the conclusion (3) is true.

Let’s try it with the DSM:

1. (What would we need to write here?)

2. The disorder is in the DSM

3. Therefore the disorder is real

We run into a problem:

In order to complete this syllogism, we could say something like “the DSM is an exhaustive list of real disorders”, but that seems to be taking the notion of the DSM as a “Bible” a bit too literally (as much as we may wish we actually had sacred texts for psychology, which would save us a lot of time).

But why isn’t the DSM an exhaustive list of real disorders? Let’s take a different point of view: if we picked any entry in the DSM, could we come up with any way for it to have been written using deductive reasoning?

Let’s pick a “random example” from the DSM-5, using CDC’s website for convenience:

To meet diagnostic criteria for ASD according to DSM-5, a child must have persistent deficits in each of three areas of social communication and interaction (see A.1. through A.3. below) plus at least two of four types of restricted, repetitive behaviors (see B.1. through B.4. below).

Persistent deficits in social communication and social interaction across multiple contexts, as manifested by the following, currently or by history (examples are illustrative, not exhaustive; see text):

Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understand relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.CDC

I’ve highlighted a few intriguing words and phrases in bold: Deficit; Normal/Abnormal; Social communication; Social interaction.

How do we define these? What does it mean to have a deficit? Do compare humans against a perfect standard of human being? Do we take the average and consider anyone below as deficient? Is there an “ideal human” that we’re all measured in steps away from?

Well… they aren’t defined

If you’ve read the spoiler above, you’ll know that the DSM is a statistical manual, in that it uses statistics such as “normal range” to delineate normal and abnormal behaviour. The statistics do change over time, and there is no reason to expect them to stay the same forever, but the most important implication is that they’re all based on what we define as a normal range (or rather, what’s not within “normal range”, in our case of disorders).

The definition of what we consider normal has been debated, especially with personality disorders, but what we’re more interested in the lack of deductive reasoning—or rather the impossibility of it. Despite its nickname, it really isn’t actually a Bible.

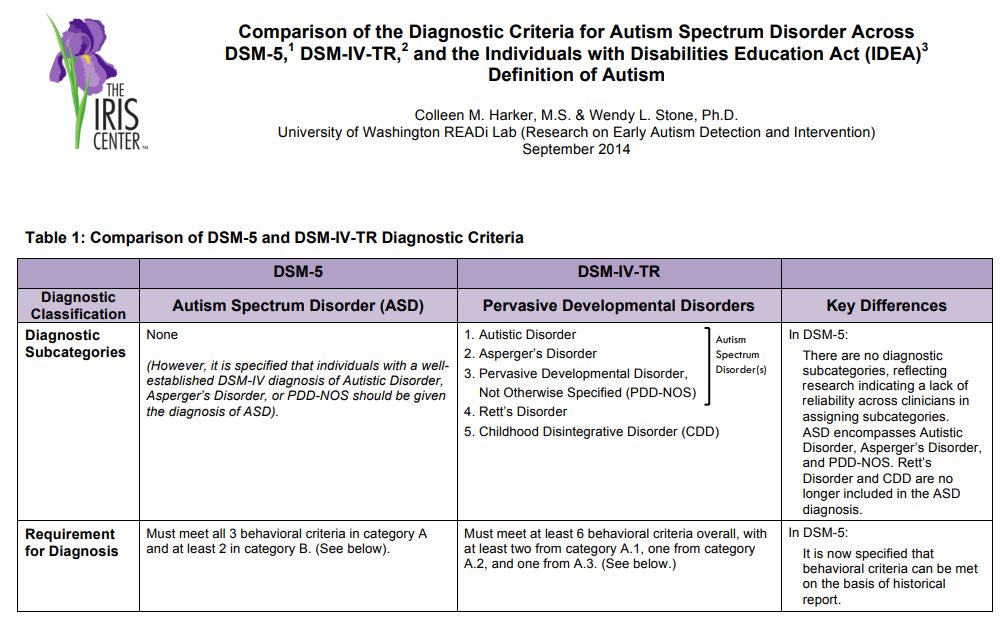

The DSM primarily reflects this ambiguity is by undergoing revisions on a somewhat regular basis (we’re currently on the DSM-5-TR), as psychiatrists update the different categorisations in order to try and correspond better with reality among other reasons (we’ll also skip over the why part of diagnoses for this discussion). A brief comparison of the differences for the diagnosis of autism since the previous major DSM revision (DSM-IV-TR) can be found below:

In short, autism isn’t “real” in the sense we can arrive at it using deductive reasoning and perfectly delineate the condition from everything else, but that doesn’t make it useless. Generalising or categorising things in everyday life such as cats (two pointed ears, whiskers, furry, four legs, paws, etc.) and being able to also predict their other unseen traits such as behaviour with good enough accuracy (they are carnivores, hiss when provoked, and hunt small animals such as birds, etc.), is useful, just as having a category for Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is useful for explaining, identifying, and predicting behaviours with reasonable accuracy.

Not all cats behave in exactly the same way, and with ASD being so heterogeneous, it’s unsurprising to see large differences between individuals, even if they still share more similarities with each other than with most other people, hence their grouping under this umbrella of traits.

Another way to think about disorders is by pondering the question: “Why do these people differ from everyone else and why do they seem to differ in the same way?”.

The purpose of the DSM—though widely misunderstood by many—is actually very simple: it’s to help those in need. And what first step is more important than narrowing down and identifying the problem?

Carrots

As psychologists continue doing research on ASD and improving our understanding of it (why are these individuals different from others in such similar ways and why do these differences exist?), we’ll be better able to describe the phenomenon and improve our definitions, updating the books as we go. Like plant identification, ASD can be a bit like classifying everyone under the “carrot” family (it’s random, I swear). We know that what we’re looking at is some kind of carrot, but we’re not sure how to further classify it, if we even should at all.

As an aside, having more precision would be fantastic, as the heterogeneity under this umbrella makes it nearly useless when trying to explain to others what it’s like; sometimes it’s even easier to completely forgo the term “autism” and pretend to be intellectually-challenged or naturally eccentric in order to avoid confusion (though not mutually exclusive with autism).

And perhaps some of us may even be more accurately classified as something other than carrots. At the moment, we do not have enough information to precisely differentiate between everyone on the spectrum, which is why we’re all still carrots, but the goal of increasing homogeneity and (perhaps thus) accuracy is unlikely to change. With ongoing research and increasing autism awareness, the future looks promising.

There are still a lot of misconceptions about mental disorders in general that aren’t related to ASD specifically, nor do they affect ASD the most—as much as some extraordinarily-noisy self-advocates may assert. For example, Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a far more serious condition that’s perhaps even more widely-misunderstood. Not only is it more prevalent (more people have it), it even has potentially fatal consequences when left untreated. We’ll come back to why mental disorders are so much harder to accept than physical disorders later.

Like mentioned in a previous post, I have no desire to take part in the war as an autism advocate. I don’t hate autism, but a lot of it is starting to feel disturbingly similar to radical feminism or third wave antiracism, where they’ve started going off the deep end in pursuit of their extreme ideologies. Judging from posts written in both autism hate sites and several autism advocacy sites, many of these so-called advocates are hardly different from the very people they’re criticising. If this is the first time you’ve heard of the existence of autism hate sites, don’t worry, just like how these “autism advocates” give autism a bad reputation and do not stand for everyone with autism, those who claim to stand for what’s “normal” or “neurotypical” do not stand for everyone else either.

The community members would post angrily on the forums about how these disabled people keep blocking their sidewalks with their wheelchairs and taking up so much space in public transport, or how they get to sit around all day instead of “making the effort” to get up and walk like everyone else, even posting videos of themselves destroying wheelchairs in order to force these inconsiderate, lazy wheelchair people to get up and walk.

A site like this isn’t likely to exist (I hope it doesn’t) but if it did, it would be amusing if only to show the variety of people in this world, and how autism doesn’t seem like that strange of a disorder in comparison. The same goes for autism hate sites: if you find yourself on one of them, perhaps you’ll find peace by thinking about a wheelchair being angrily propelled with unbelievable velocity across the room.

As for the “self-advocates” who write like innocent victims suffering from perpetual indignation (you’ll know when you see them; I can’t stand them), let’s describe them using a phrase that will no doubt cause them to lose their minds: autistic screeching.

Not only are they giving people with autism a bad reputation on the internet, their posts are rarely if ever actually informative more than wastefully (and aggravatingly) self-aggrandising. Though what I’m saying isn’t true for all autism advocates (generalisations are never true, including this one) and there are many very well-written posts which I will link in the sympathy discussion below, I find those who believe that they’re superior, that the world “owes” them, or that they’re born victims of… something, absolutely insufferable.

I worry for the younger, relatively-impressionable individuals with autism, who may start developing erroneous ideas about the world that are hardly centred in reality, in turn acting like self-centred narcissists, causing people to actually hate them, then blaming it on prejudice. Regardless of age—even if it has been suggested that people with ASD are more rational—humility matters far more when it comes to seeing the world objectively, something these writers seem to be sorely lacking.

The portrayal of autism in media

One critique the entertainment industry often receives when it comes to portraying autism is their focus on savants. Some people have found a way to take it as a personal insult, accusing them of implying that anyone who isn’t a savant has no use in society—in other words the majority of those with autism—but is really true? Is this really the message?

Additionally, you’ll also have many who will claim that the portrayal isn’t accurate because it doesn’t correspond to their personal experience. Though there is an argument to be made against the exclusive portrayal of savants given that they only represent a minority of those with ASD, judging characters based on how similar they are to one’s personal experience is equivalent to shooting oneself in the foot by denying the heterogeneity in ASD.

For many of these people, the fact a character was “written by neurotypical people” or “portrayed by neurotypical people” also automatically disqualifies a character from being accurate. This has some silly implications when applied more fairly to also include other disorders, as it suggests that neurotypical people shouldn’t write any non-neurotypical characters, period, regardless of how much effort they put into researching whatever it is they want to portray.

Is fiction usually accurate?

Badly-written characters do exist—and autistic characters can be more likely than neurotypical characters to be badly-written—but the argument “it’s written by a neurotypical person” should not be sufficient in and of itself to dismiss a piece of work. Plus, since when was fiction about accuracy anyway? It’s as if people expect to be educated as a side effect of being entertained.

Think about the last time doctors, lawyers, police, musicians, even scientists were portrayed accurately—you’ve all seen those cases

“The law doesn’t work like that.”

“Are the police really allowed to do that?”

“Why is that violinist playing so quickly during the slow sections?”

“What happened to the laws of physics?”

This doesn’t mean that one shouldn’t write fictional yet accurate stories. If creativity shouldn’t be restricted to only facts, then why should this restriction apply the other way round? Writers should be allowed to write stories with as much or as little accuracy as they want. Whether their writing is well-received and supported by the public depends on the local era and context, but that choice should still be left to them.

A bad piece of work can and perhaps should just be ignored. In fact, most of them are, that is until they accidentally touch on a trendy political issue. In that case, it’s suddenly justified to form an angry mob, send threats of violence and harass them as if the existence of the work is in itself a personal insult. As much as feedback—including negative feedback—can helpful, devolving into needless, angry censorship is hardly what I would consider useful.

I don’t get all wound up when I watch Star Wars because of how inaccurately it portrays physics (they’re plasma cutters), but I still appreciate shows that try their best to be as accurate as possible, like in The Expanse (which still has its fair share of inaccuracies!). The same goes for autism: accuracy is always appreciated, but a lack of it doesn’t mean I have to immediately storm out the door with a pitchfork. Not every error is intentional; even documentaries get things wrong sometimes.

If a writer (or even actor) is nervous about whether their portrayal of autism is accurate, it should be because an accurate portrayal is what they want to achieve—not because they’re afraid that they’ll get harassed, mocked, and ostracised if they fail to do so (or worse, fired).

But, cynically, that may just be how the world works. Even as I’m writing this, I’m nervous about juxtaposing this with the ironic public acceptance of religion not because I’m afraid that it’s an inaccurate comparison, but because of the potential backlash. Religion is infamous for a history of killings after all, and many were burned at the stake for even having dared question it. If the public were really that concerned about accuracy and being in line with reality, why aren’t they addressing the elephant in the room?

Going back to savants

Anyway, back to savants. Even in real life, you’ll find that most well-known autistic people are savants. Why? The answer is a lot less complicated than it seems: they’re very interesting. Ignoring the downsides of autism, these people possess the equivalent of “superpowers”. Superpowers? In real life? That’s interesting!

The majority of savants—the ones with these “superpowers”—have autism, which is the most likely explanation for why they’re so often portrayed with it. Autism may very well have nothing to do with the characters’ fundamental inspiration, since they tend to be primarily written around their savant abilities—a real life, non-fiction superpower, having the story plausibly set in our world instead of in a galaxy far, far away. This may seem shallow, but it’s not that different from how we usually envision others we like or look up to, often remembering them for their strengths before their weaknesses.

Even if this wasn’t the case and the writers were genuinely interested in accurately portraying autism, it’s not easy to write a character so foreign to one’s own experiences, making it very important to also consider the writer’s perspective and intentions before (perhaps unfairly) disparaging them for writing badly-written or offensive content, a reaction especially discouraging to those who have actually put in a lot of effort and research trying to portray the condition accuracy.

For one, I can’t write a neurotypical character without unintentionally introducing some oddities and inaccuracies because I don’t fundamentally think like this character, and this is in spite of interacting with so many neurotypical people on a regular basis. If a writer without autism can write an autistic character that gets most of it right, they should be praised for putting in the effort instead of bitterly disparaged for their minor inaccuracies, and this includes the actors who put in similar effort and get so much of it correct.

Due to the necessity of fitting in, I play a neurotypical character on a regular basis—what is referred to as masking—and, even after so many years of practice, it’s still nowhere close to being perfect (though it’s still good enough). If the same kinds of criticism were leveraged against autistic individuals for minor inaccuracies in their neurotypical portrayals (that’s not how we neurotypical people actually behave!), we would all be in trouble.

It might even be that masking only works because of the lack of autism awareness, in that people aren’t likely to suspect autism when they meet someone with minor oddities. It would be much harder to mask if everyone learned how to accurately differentiate between “this person is a bit strange” and “this person has autism and is clearly pretending otherwise”, but this is unlikely to happen for reasons I’ll discuss below (regarding the limits of autism awareness and acceptance).

The purpose of entertainment

The purpose of entertainment is, first and foremost, to entertain. For knowledge and education-based forms of media, we have documentaries and non-fiction books, although many can be sufficiently entertaining in their own right. That being said, a perhaps concerning number of people do treat entertainment media as a primary source of knowledge (and yes, this does include social media), which in turn starts placing stress on producers of entertainment to also be educational (which isn’t their primary domain to begin with).

Let’s try and write a character. For the sake of simplicity, we’ll limit our character to only the milder end of the spectrum—high-functioning enough to be able to pass as normal, or create needless drama on the internet.

What would our character look like? If we assume the capabilities of the “typical” high-functioning autistic person, they’re probably able to convincingly mask in front of others. So, what would they look like? They’d look like everyone else, wouldn’t they? Normal?

Though they mask when they’re interacting with others, what about when they’re not interacting with others, like when they’re alone? Well, they’d still look normal, wouldn’t they? You can’t look at someone reading a book in their room and go “that person has autism”, given that problems with social interaction aren’t really demonstrated in situations without social interaction, for obvious reasons.

So they’d look normal regardless, unless we tried an “inner narrator” approach like in You in order to show the audience how this normal-looking person isn’t actually normal at all on the inside (this was the best depiction of masking I’ve seen in recent mainstream media, and it wasn’t even about autism).

But without some kind of exposition like this, it’s pretty boring, isn’t it? And not all movies or shows are compatible with this method of storytelling. Instead, you’ll just have a normal-looking person with nothing particularly special going on except for being “slightly weird”. It may be a story about autism, but what the audience sees most of the time is just a typical, boring individual. Accurate, but not very entertaining, and still better suited for documentaries instead.

That’s why autism usually always portrayed with some kind of visible symptom, such as various tics or abnormal movements, in order for the audience to actually “see” the autism, sacrificing accuracy for exposition. This alone isn’t enough for entertainment, of course, because what we get is still more or less your typical person who moves a bit weird, that’s why the rare savant syndrome is so often depicted in conjunction in order to make things more interesting.

That said, the fact autism is so often portrayed as a visible disorder with characters who somehow all make it to adulthood before learning how to mask can cause misconceptions. It might suggest to them that autism is a visible condition which makes them believe they are able to identify someone with ASD just by looking. “But you don’t look autistic” is a very common response to someone with mild autism opening up about their diagnosis, for example.

In a recent Korean drama featuring autism “Extraordinary Attorney Woo“, our main character somehow makes it all the way to adulthood without masking. It’s a bit unbelievable, though it was nothing compared to suspending my disbelief for 1.5 MCU movies before collapsing.

A scene that stood out to me in one of the early episodes was one where she stopped talking about whales in front of others after only being told to stop once… as in you’re saying she made it all the way through university and adulthood talking about whales and nobody even told her to stop once? Once was all she needed!Similarly, in Good Doctor (2013), the main character only starts masking towards the end of the series, slowly beginning to appear more and more like everyone else.

But, I still get that it’s far more interesting portraying someone still learning how to mask than someone who’s already able to pass as slightly awkward, as much as the latter may be a more accurate depiction of how autism actually looks in real life.

Although this is not a documentary, the writers seem to have done a lot of research, even clarifying the spectrum part of ASD, and demonstrating (via the main character) how not everyone on the spectrum is alike and can understand each other.

This is very optimistic proof for how far autism awareness has progressed since just a few decades ago, in spite of certain autistic people who seem hell-bent on portraying it as a form of narcissism or self-aggrandisation.

In the next part, we will continue by exploring masking and empathy in autism.