Further continuation of the series on disclaimers, this time with more of a focus on my personal thoughts (hence unlinked from the previous posts).

The level I comprehend and understand philosophy and its related studies are not as erudite as many others, which limits me to a rather amateur, dilettante style of writing.

This limitation creates an otherwise unnecessary need for excessive caveats and disclaimers due to its relative lack of precision and clarity compared with denser, more erudite material that uses advanced vocabulary and complex ideas to skillfully maneuver and elucidate their arguments with little remaining doubt—hence reducing the need for further unnecessary clarification.

That is, of course, not to say that they don’t clarify, but rather that they need not use as much as a result of already being clear and concise in the first place.

As the first post about self-esteem addresses, the fact I feel the constant need to clarify myself and prematurely defend myself from criticism (the fact comments are disabled at the point of writing only further suggests that the criticism I’m receiving is largely imaginary and delusionary in nature) also suggests the possibility that this concern with both criticism and caveats, disclaimers, and the like are possibly issues of little consequence, assuming my skewed motivation is the main proponent of this otherwise unfounded worry.

The Principle of charity

One of the main criticisms I feel I cannot adequately address is that of open-mindedness, at least the interpretation that we should consider every proposition equally and fairly. The Principle of charity comes to mind:

Of course, if everyone acts like this, there would be even less reason for the use of caveats unless absolutely necessary, but as with the previous post we cannot assume that everyone is capable of the same knowledge and critical thinking ability, hence rendering this less effective than it could be.

The disparity in knowledge and understanding in authors and their readers can result in a fundamental mismatch of interpretation. A reader, applying this principle, could come up with an understanding far more advanced than the author’s intention, while assuming that this is what the author really meant.

This reader may, as a result, become confused when talking to the author, as the author appears to not understand “their own” argument (from experience, this occurs more when the proponents are careless laypeople, which sometimes causes a bit of frustration).

The converse also occurs: the readers may be unable to find a sufficiently-charitable interpretation of the author’s argument and remain unconvinced. This is what I believe authors try to avoid in their use of disclaimers and caveats, in order to aid the reader closer to the author’s understanding of the topic at hand and prematurely eliminating erroneous conclusions and unnecessary misunderstandings.

Closed-mindedness

There are limits to what one can accept, many believe that a refusal to entertain their pet belief is not unlike being “closed-minded”, using it as an argument to persuade (taunt) others into considering their beliefs, but this isn’t necessarily the whole picture.

If somebody, for example, tells me that the Moon is actually the corpse of the dead Sun rising back up only to be revived the next day (this example is from Pinker’s Enlightenment Now), would it be more reasonable for me to abandon all prior knowledge in astronomy and seriously consider this belief in order to maintain my position as an “open-minded” person?

For starters, if this person tells me that the Sun sometimes makes a ghastly sound when killed, I could stake out an evening listening for it. Of course, I would find nothing, but I’d be reassured that it would happen eventually. One day, right as the Sun sets, I hear the sound of what was really a wild animal in the distance. Excited upon hearing the noise, I’m told that the Sun has just been killed.

This goes on and on, even explaining how the Moon has different shapes each time because it’s killed in different ways.

For readers with a basic understanding of astronomy, this is ludicrous drivel, but on what grounds can we dismiss it so quickly without giving it fair consideration?

Is it that we know better and are unwilling to part with our relatively advanced understanding of basic astronomy? Or is it because this alternate hypothesis is far too unreasonable to be worth considering?

If you think about it, despite being faulty and riddled with fallacies, it still is “reason”. The Sun going down in the West and the sky going dark at the same time could suggest that something has happened to the Sun, but what?

If we look at the Moon, it appears to change shape every time it comes up, and follows the same trajectory as the Sun. Using nothing else but these observations, one might perhaps not-so-unreasonably conclude that something has happened to the Sun that turned it into a Moon, and the fact it’s gone dark might mean it’s been killed, sometimes even brutally, as evidenced by what’s left of it each time.

The problem with rationality and reason is that it’s also possible to reason oneself into absurd positions, which can tends to happen more often than not when people independently rationalise instead of engaging with others in controlled debates.

Our knowledge of the many flaws in our cognitive faculties and reasoning including biases, heuristics, and fallacies, is easier managed in groups of thinkers who all agree to look out for it in each other, in order to compensate for the lack of self-awareness these biases can result in.

In short, scientific communities were formed in an effort to help everyone increase their rates of forming accurate, reality-conforming conclusions as opposed to the random noise that one might otherwise invent when left to their own devices. From my personal experience, the most inane arguments and beliefs come from extremely intelligent people who seem to be able to justify just about anything using their elevated reasoning ability; something I’m not always sure how to react to: whether with laughter or with despair. The ability to rationalise anything can produce some very interesting results, as with many of my pet theories.

Going back to the point, what grounds does one have for dismissing an “absurd” belief if one really claims to be “open-minded”?

I could spend half an hour reading the introductory chapters of an Astronomy textbook, or I could spend several days listening for the sound of the Sun being killed by creatures in the West, which is a much lengthier process.

Am I, then, only choosing our conventional knowledge of Astronomy because it is faster and more convenient? Keep in mind, though this knowledge was built over many millennia, I haven’t the means to verify it firsthand, assuming my senses can be relied on. Still, I find the claim that the Moon is the corpse of a dead Sun absurd (a telescope might not disprove this as easily as one might think, since they would still be able to argue that the image in the telescope is indeed not a “Moon” but a dead Sun.)

Back to the point

So what makes Astronomy special compared to some folk tale about the Sun? Both use reasoning, and both can be considered “rational” (the Moon following the same trajectory could suggest that it is the Sun), but the difference with science—more precisely the scientific method—is that our reasoning is as controlled as possible, putting in our best efforts to find an explanation that aligns most closely with reality. Hypotheses are challenged, findings are refuted, scientists quickly move on from previous ideas in favour of those that corresponds more closely with reality.

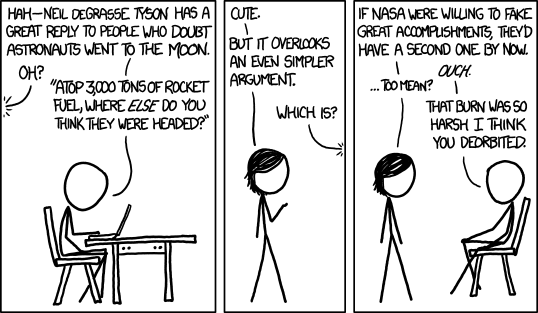

I don’t know what reason I would have to believe that the Earth not being flat is a conspiracy only that it is absurd, but if thoroughly questioned I cannot confidently explain why I believe so other than the conviction that so many people could not possibly come up with such an elaborate, collective lie, and there’s a lot of stuff they have to have collectively lied about across many generations, somehow all cooperating and converging on the same lie and never being detected (where are these generations of people holding these secret conspiracy meetings?).

The purpose of it would be absurd. As someone once said about the footage of the Moon landing: “given how elaborate the lie would have to be, it would have been easier for NASA to just have gone to the moon”

Dismissing an opponent’s claim on the grounds of it being far too unlikely or reasonable is still not giving them the full benefit of the doubt, but if we were to consider everything regardless of how unlikely or absurd they may be, then we would spend our lives in eternal turmoil, wasting precious time and resources on probabilistically-useless beliefs. After all, even if I were sent to space and saw the Earth’s curvature for myself, one might still argue that I have been deceived by my senses and that there was some special device that alters my vision inside the spacecraft.

Closing

Anyway, these alternate hypotheses are unfalsifiable, case dismissed (sorry Paul Feyeraband, not today). If I had infinite processing power and time I might be able to consider any and everything, but as a human being with limited time and resources, I’m afraid I’ll have to deny considering unfalsifiable and superlatively improbable scenarios—scenarios impossible and far removed from reasonable doubt.

Though I intended this to be the last of these posts, I’ve skimmed over several new, unintentional topics for the sake of brevity, potentially furthering any suspicion that I possess no more than a cursory knowledge on these subjects (other than Astronomy, which I genuinely know very little about). Granted, this suspicion is internal, but I do have grounds for believing so, having lived a life of being misunderstood and never quite finding the right words. One of the superpowers I wished I had when I was younger was not the ability to read others’ minds, but rather for others to be able to read mine.