A somewhat disorganised post on my expectations of knowledge for both myself and others

Myself

I don’t consider myself an avid reader by any means. The book list I have on my website is quite accurate: it really does take me a few weeks to finish books. I used to spend a lot of time on online resources such as Wikipedia and the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, reading through studies cited in the references and finding books to read, but I stopped doing that at some point.

Outside the current book I’m taking my time reading (Behave by Robert Sapolsky), the open tabs on my phone that used to be more reading material have turned into leftover dictionary searches for words I’m worried I’ll forget like superable, panoply, and aver. Most of what I’ve been doing with my free time instead has been watching YouTube/Netflix and playing computer games, which isn’t exactly the kind of life I envisioned after recovering from depression.

I thought I’d be more motivated to read, but now that things are better it’s as if I’ve lost the urgency to continue trying to understand the world. One wrong step and I might even start using social media like everyone else. Which, to be honest, I’ve been really tempted to do as of late. All of this instead of reading.

Another misconception I shouldn’t have had but had anyway was that all my knowledge accumulated so far would simply stagnate, but if only life were so easy—knowledge doesn’t just stagnate; it decays. While reading the first few chapters of Behave—the introduction to neurobiology—I started to realise things that shouldn’t be realisations at all had I remembered what I read less than half a decade ago. It was very disappointing to see how much I had forgotten over the years, and for the consequences to have cost me a significant, potentially life-changing opportunity because I led myself on a wild goose chase instead of remembering the basics of brain function before proceeding any further; completely forgetting about habituation, I used an inaccurate, intuitive substitute conjecture, and only realised what I should’ve done long after the opportunity was gone.

But, hindsight is hindsight, and I was completely convinced I had exhausted all my options back then. Not knowing what it was called didn’t help either. I can’t bear to imagine how much I’ve missed in my life so far as a result of forgetting basic brain functions like this. Not knowing something doesn’t hurt; it’s always good to learn new things, but forgetting something important is an indictment against myself. I should’ve known better.

And others

I can’t speak for others, though there are many who seemingly aren’t aware of this. People believe what they want to believe, and if someone wants to reduce their feelings of uncertainty on whether they’re correct, one easy solution is to imagine everyone else is on their side.

Common expressions include “I think I speak for everyone when I say…” or “People like us…”. There are more contributing factors and they all play some role in why people are naturally inclined to believe the group they identify with is on the same side as them, but intuition is terrible at maths and drops nuances faster than DJs drop the beat. After all, its main selling point is speed; not accuracy.

I started this post by saying that I’m not an avid reader seemingly out of the blue. This may be hard to believe—and I believe I can do way better—but I’ve been called an avid reader by others on several occasions, and I don’t know why. Perhaps I do read more than most people—almost exclusively non-fiction—but I still hardly read compared to how much time I spend not reading, or compared to people who mostly read fiction which I find incomparably challenging to read. How do these people even finish one book a week?

It took me several months to finish The Hunger Games trilogy. By the time I got halfway through Mockingjay, I was already completely lost with at least five different interpretations of what the world looked like at that point. A few years later, I tried reading To Kill a Mockingbird, thinking that it must be easy to read given how popular it was. I was wrong. By the end of the book, the image in my head had their house and a church in a superposition, along with a road that went straight back towards where it started as if the universe was looped into itself. It took me 6 weeks to read To Kill a Mockingbird, and it was only about half as long as the typical non-fiction book. I hate fiction.

Either way, the majority of people do not read. From an avid reader’s perspective, I may not seem like an avid reader at all, but from the typical young adult growing up with social media and the internet who often wonders why anyone wastes their time reading books when they can just use Google, people who read at all are somewhere on their list of pejoratives I don’t quite understand.

Pearls before swine

Not the comic (which is hilarious), but the idiom. Reading the comments for YouTube videos, especially general science and education ones, can sometimes lead one to wonder if there was even any point to the video, as if casting pearls before swine—an audience without the ability to comprehend to appreciate the topic.

There is a spectrum, and of course there are exceptions. Some videos are badly-presented, some intentionally deceptive, and some unequivocably full of nonsense, so it’s not fair to say that an audience not being able to grasp the topic is a smoking gun. An example of a channel that’s become notorious as of late is Sabine Hossenfelder’s which for whatever reason seems to attract commentators who know just enough to both be fooled and fool other unsuspecting viewers with their superficial understanding of the topics discussed. A ticking time bomb.

Effective science communication involves more than merely reading out papers; it’s equally if not more important to lead by example. People are attracted to things like them, and if one only seems to attract the worst of people, perhaps it’s time for some self-reflection. I wonder what kind of people I attract now… perhaps it’s time I do some self-reflection on whether I’ve really presented the best example of critical thinking behaviour, or if I’ve only managed to appeal to those who have no interest in learning how to think more objectively and fairly.

Another proverb: “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” Teaching shouldn’t be limited to just giving out facts. It’s crucial students be taught how to think so they can one day go out on their own and develop objective, balanced, and fair views based on scientific evidence while still keeping in mind the limitations of the scientific method, always ready to change their beliefs when presented with stronger evidence for an alternative, and acting on probabilities rather than absolutes in this ostensibly undeterministic (inconsequentially-deterministic) world.

There is a strong preference for knowing the “what” over the “how” in education worldwide. Students are rewarded for the former, and hardly recognised for the latter. The irony of science is that while the “what” changes constantly, the “how” remains remarkably stable over time. We end up with students loaded with false, outdated information who barely have any experience correcting them. Why, then, is the focus not on the latter? Critical thinking should be introduced in preschool, not university.

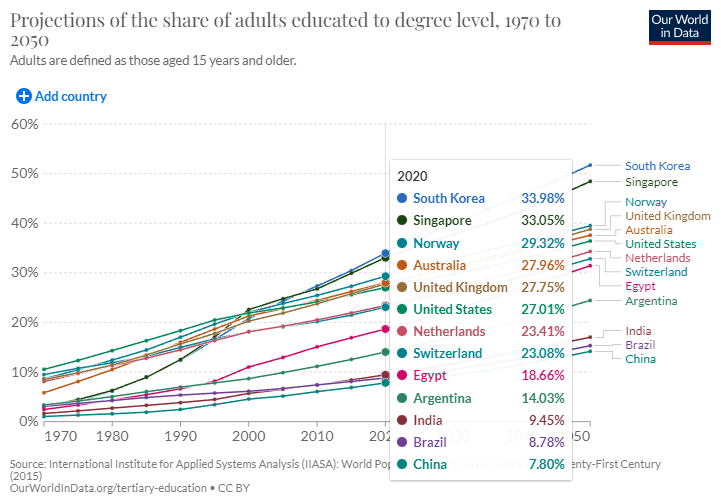

There are caveats to this projection (more information: Tertiary Education – Our World in Data) so take the numbers loosely.

There are limits to what we can conclude from this, but I think it’s safe to say there’s a lot to be gained from children being first given a solid foundation in the scientific method before being forced to choke down rote learning tasks. I don’t believe that children are incapable of learning how to think, and I believe that it’s far more productive use of their time—even if more challenging—than memorising information so useless they’ll have forgotten them five seconds after leaving the exam room.

Deliberately-false information should be presented as true in both classrooms and textbooks from time to time so children can get used to the habit of thinking critically and get used to the fact that even “trusted sources” can be wrong sometimes, but not so often and so hard to spot to the point they give up in frustration and go “I don’t know what to believe anymore”. That said, “I don’t know” is a valid answer, and students should be rewarded for it.

There should be questions about controversial and highly-nuanced topics in exams where “I don’t know” is a perfectly correct answer after considering arguments from both sides. Currently, the system has every of these topics polarised for no reason other than “it’s easier to mark papers that way”. Alternatively, perhaps someone confused the “propagation of education” with the “propaganda that is education” when asked to design the system.

Of course, it’s possible all of this just comes down to personality—having a higher need for cognition for lack of a better description heavily biases the way I look at things. Perhaps people genuinely just don’t want to think and would take rote learning over it any day.

It’s going to be very challenging to make this argument without saying something along the lines of “thinking is fun”, therefore we should teach our children how to think. I don’t like football. If someone tells me about how much fun football is and how we should all teach our children football, wouldn’t their proposal be equally (un)justified?